The Sufi Freedom Fighter Who Inspired the Lubavitcher Rebbe

How did the song of a Muslim Imam from the Caucasus Mountains become a Hassidic niggun [song] in the Rebbe’s court in Brooklyn?

“Speech is the quill of the heart, and song is the quill of the soul” (Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi)

Simchat Torah evening, 1958, Brooklyn, New York. The central study hall of the Lubavitch Hassidut in the Crown Heights neighborhood is bustling with activity. The Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, stands in the center singing a new niggun. For a decade, beginning in 1954, the leader of the Hassidut would teach his disciples an unfamiliar Hassidic tune from days gone by. On the festival evening, following the traditional Simchat Torah hakafot [dancing around the synagogue 7 times with the Torah scrolls] and the festive meal, when the Hassidim gathered together for a “Hitva’adut [which means coming together or bonding]”, he turned to the crowd and said:

“I heard this tune from Hassidim, together with a story. When the Russian government began to expand by capturing large territories, they set their sights on the Caucasus Mountains which were inhabited by uncultured people [on another occasion, when talking about this song, he said “Semi-barbaric tribes, who were as free as a bird, with no laws, and even without cultural restrictions”], who had their own Emperor whose name was ‘Shamil’. Despite the government’s numerical advantage over these mountain dwellers they were unable to conquer them due to the difficulty in reaching them, as they lived in high mountains. Until they tricked them – they promised to make peace with them, and to grant them leniencies and so forth…and they eventually captured the ruler ‘Shamil’, and exiled him to the depths of Russia, and whether he was imprisoned or not, he was in exile.

When he was in exile, he would occasionally remember the high mountains where he was free of the bonds of government, without the restrictions of the jail and even without the restraints of a settled city of residence and the limitations and constraints of culture, and now he is enslaved…and a great yearning for those high mountains, where he was as free as an eagle in the heavens would awaken in him, and he would sing this song, which begins with yearning and ends with hope that he will eventually return home.” https://www.youtube.com/embed/enx_y5l9JZI?feature=oembed&enablejsapi=1&origin=https%3A%2F%2Fblog.nli.org.il

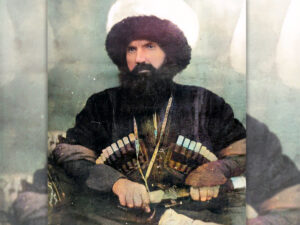

Who was Shamil? What is known about him? Imam Shamil (1797-1871), was a tribal leader in North Caucasus, a Sufi Muslim, politician and rebel, who led a stubborn battle against the Russian desire to expand their empire by conquering land in the Caucasus region. At the end of a long, drawn-out fight, Shamil surrendered to the Russian troops and was imprisoned in a small village in Dagestan. He was later exiled to the city of Kaluga, a small city in central Russia, not far from Moscow. In 1869 the Russians permitted Shamil to end his life in Mecca, and he travelled there via Istanbul.

Shamil died in Medina in 1871 during a visit to the city and was buried in “Jannatul Baqi”, a famous cemetery in Medina in which many famous personalities from the Arab-Muslim world are interred. Shamil was, and remains, revered by many of his followers. His courage, bravery and determination became famous among his admirers.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel’s account of Shamil’s story is consistent with the historical facts, but what about the song which “begins with yearning and ends with hope”? Is its source known? Is the song known and sung in different Caucasian communities? Seven years ago, in an attempt to discover the tune’s source, I approached Rabbi Yehoshua Mondshine, an esteemed researcher of Hassidut who worked for many years as a senior librarian in the National Library’s manuscript department and archives. “I doubt that the information I have will bring you closer to your goal,” he said, “I heard from the Hassid Avraham Mauer (Dreizen) that in 1969, while walking through the Boro Park neighborhood, he saw a non-Jew watering his garden while humming Shamil’s niggun to himself.

Mauer claims that the non-Jew knew the song from a foreign source, but did not remember if this is what he heard from the non-Jew after asking him, or if he recognized from the tune itself that it was similar but not identical to that taught by the Lubavitcher Rebbe.” The question of the song’s source remained, “Perhaps you should search in the field of theatre?” Mondshine suggested, “I know, for example, that a movie was made about one rebel – Pugachev, so perhaps a play was produced about Shamil, in which that song is the background music when he is in jail? Logically, the chances of knowing what Shamil really sang when he was imprisoned are miniscule, and only a song publicized by a play could become known and travel great distances.”

Mondshine’s proposal to attempt to locate the song’s source in theatrical productions or Russian movies was seconded by Professor Edwin Seroussi from the Hebrew University’s faculty of Music and director of the Jewish Music Research Center. “This song has interested me for many years. The Lubavitcher Rebbe said that he heard the tune from Hassidim, I assume that the Jews who sang the song to him lived in the Russian region. The song’s musical components are different than those traditionally found in regular Hassidic niggunim, and especially from Lubavitch niggunim. The Russians were fascinated by Shamil, and his character appears in late 19th century and early 20th century Russian literature. It is possible that this tune was used as background music for a movie or a play. Jews were members of the Russian upper class and it is likely that they were familiar with this literature and with Shamil’s role. I have no concrete proof of this as I have yet to carry out a detailed investigation which requires high proficiency in the Russian language, but my instinct tells me that this is the correct approach.”

Professor Seroussi also discussed the song’s musical character, “Years ago, I worked on a collection of music of the Mountain Jews together with the musician Peretz Eliyahu who is a great expert in the field. We discussed various songs in Caucasian music which are connected to Shamil. This tune which is attributed to Shamil is unknown in the repertoire. Peretz even said that ‘This is an Ashkenazi song’… the song’s character is unique and stands out among the Lubavitch niggunim. Its melodic line has a special form in an unusually wide range for a short tune, rising, then dropping sharply and then rising another octave [a musical interval of six tones –T.Z.]. This special melodic movement is undoubtedly what caused the Rebbe to interpret the song as he interpreted it.”

“The entire story of Shamil is only a parable,” Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn said to his followers, “which was created in order to derive the niggun and the moral for service of God from it”. The story of Shamil’s niggun can be seen as a metaphor for a Jew’s soul. The soul, which is inherently spiritual and abstract, descends from the elevated world into our physical world and is clothed in the body of a human being. The physical body, with its needs and desires, can restrict the soul and, become a type of jail cell for it. The soul constantly yearns for the spiritual freedom and pleasure which it experienced before descending into the world. The song of yearning sung by Shamil can mirror the soul’s yearning for its source.

In an essay which will be published in the near future in the “Studia Judaica” journal, the central journal for Jewish studies in Poland, Professor Seroussi relates an interesting story connected to the “Shamil” niggun. It appears that there are some inaccuracies in the story (as it originally appeared in the compilation “Niggun: Stories Behind the Chasidic Songs That Inspire Jews” by Mordechai Stainman), however, it seems that the story’s main facts are correct – according to the testimony of one of its central participants, Shmuel Spritzer, who confirmed the story to Professor Seroussi.

The story’s central figure is the famous musician, composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein and his encounter with “Shamil’s Niggun”. The story was related by Shmuel Spritzer, who was a young man at the time (in 1970) who had come to do outreach work together with his friend Shmuel Langsam in Portland (Oregon), U.S.A. The pair, “with the black suits and hats” participated in an event held in the house of a musician by the name of Professor Bloch, waiting for the arrival of “a beloved and long-time friend” named Leonard Bernstein. When Bernstein arrived shortly before sunset, Spritzer (who did not know who Bernstein was, despite him being famous at the time) asked him to put on Tefillin. Bernstein refused.

Spritzer began to question Bernstein. “What is your profession?” he asked, and Bernstein replied, “I am a conductor”. Bernstein then asked the pair to sing something. Spritzer replied that he does not want to sing, but would be happy to play a piece of music – “Shamil” from a record which he had with him. Spritzer related that he chose this piece because of a story he had heard about the song’s recording in 1936. The violin player who took part in the recording, a non-Jewish professional musician, related that he began to sweat and experienced strange physical sensations when playing the song, and that he played in a special, different and moving manner in that recording. “You know,” Bernstein said to those present in the room, “as a Jew, I carry a lot of music in my soul.” “Then you are in the right place,” Spritzer said. “How do you know?” Bernstein asked, and Spritzer replied, “Because even your sigh is heard in Heaven, just like Shamil’s sigh.” “Who is Shamil?” Bernstein inquired, and Shpritzer responded “You will meet him in the song. The two of you have much in common”. Bernstein listened to the song attentively and said, “I like this song, I feel connected to this song, I don’t know how to explain it but I felt a feeling of release.” “I’ll explain it to you” Spritzer said, “but first, put on Tefillin”. Sunset was only a few short minutes away and Bernstein turned to Spritzer and said, “There is something I must understand, why did you choose this specific song?” “Because I like it and I felt that you needed to hear it,” Spritzer said. “You understand music,” Bernstein said, “I will put on Tefillin if you promise me that you will work in music in the future.” Spritzer agreed and Bernstein put on Tefillin for the first time in his life.

Years later, Bernstein’s travels took him to Boston. He was once again offered to put on Tefillin, this time Bernstein agreed. As the Rabbi helped him to put on the Tefillin, he asked Bernstein if this is his first time putting on Tefillin. “No,” Bernstein replied, “a decade ago, one summer evening, when I heard Shamil’s niggun.” The Rabbi smiled and said, “Yes, Shamil’s niggun.” “At that time, I heard a deep internal call,” Bernstein said, “I heard Shamil, I heard myself, I heard… that was the first time I put on Tefillin.”

In the spirit of “Shamil”‘s niggun, here is a different niggun to the words from Chapter 63 of Psalms [English translation from www.chabad.org] “My soul thirsts for You; my flesh longs for You, in an arid and thirsty land, without water: As I saw You in the Sanctuary, [so do I long] to see Your strength and Your glory”, performed by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn.

(Source)